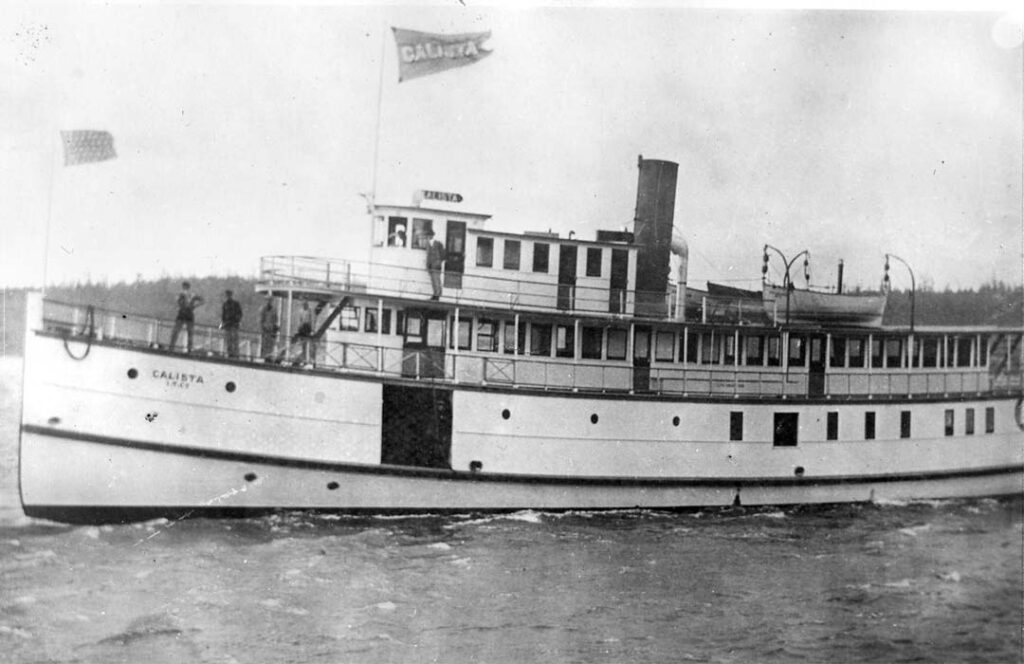

Above: The sternwheeler Fairhaven, seen here at the Langley Wharf, was an early member of the “Mosquito Fleet” that brought passengers and freight to Whidbey and Camano Islands. Circa 1910. Photo: South Whidbey Historical Museum.

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

Ever since there have been people in the Pacific Northwest, the waterways have served as transportation corridors. From time immemorial through the early 1900s, entire Coast Salish families would travel incredible distances in ocean-going canoes. Canoes were not merely vehicles but a unique art form and symbol of cultural identity. The first people often traveled to other areas for trade, seasonal camps, or visiting family and friends. When white settlers came to the region they also benefitted from Tribal canoes and the local knowledge of their paddlers, yet still the Tribes were pressured to abandon their ancient traditions.,

At one time there had been thousands of canoes regularly traversing the waterways, but by the early 1900s, there was a great risk of losing this way of life altogether, as steamships became the new normal for traveling the Sound. It was around this same time, however, that canoe racing by Native American paddlers became very popular and new vessels were crafted. In 1930 Coupeville hosted a festival featuring these races that evolved over the years to become the annual Penn Cove Water Festival, celebrating Native culture and still featuring the incredible canoe racing today.

When European explorers first entered the waterways around Whidbey and Camano Islands, it was via four five-masted timber schooners. Over a stretch of two hundred years, British and Spanish explorers searched the waterways of the Salish Sea in search of the Northwest Passage. This fabled route was imagined to be a direct sea lane from Northern China to Europe, which would have transformed trade routes of the globe. Many familiar names-such as Juan de Fuca, Vancouver, Whidbey, and Camano-come from the explorers that chased that dream to the waters of Puget Sound, until ultimately concluding such a passage didn’t exist. What they found instead were incredibly fertile lands and waterways that their nations were eager to claim as their own, with no regard for the land having already been inhabited for thousands of years. Many of the hand-drawn maps created by these early explorers are remarkably accurate.

It wasn’t until the mid-1800s that Whidbey and Camano Islands began to see permanent white settlers, initially drawn mostly for timber resources. As small towns formed along the coastlines, several long wharves came and went over the years; with sand bars and storm tides creating challenges. Between the 1880s and 1920s, a giant collection of steamships operated around Puget Sound. Known at the Mosquito Fleet, they served as a primary form of transportation and fueled the growth of the area by reaching just about anywhere with a waterfront.

Camano Island didn’t have a bridge attaching it to the mainland until 1913, and Deception Pass Bridge wouldn’t connect North Whidbey to Fidalgo Island and the mainland until 1935. There was no ferry service to the islands until the mid-1920s, so the Mosquito Fleet steamers were the only option unless one had their own boat. For quite some time there was daily service out of ports like Seattle, Everett, or La Conner, making stops at Clinton, Langley, Coupeville, Oak Harbor, and Utsalady. The islands have long been popular places to visit, and residents had access to many retail goods thanks to their proximity to the busy marine shipping lanes.

While steamers supported the hustle and bustle of trade and transport, there were other ships built simply for pleasure cruising. Whidbey resident Frank J. Pratt Jr. came to the island in 1905 and owned much of the land now known as Ebey’s Landing, including the Ferry House. In 1925 he commissioned the build of a 68ft wooden schooner for sailing trips with his family. The schooner SUVA is just as grand a vessel today, with old growth Burmese Teak construction which has been lovingly maintained by the Whidbey Island Maritime Heritage Foundation. Passengers can still enjoy sailing tours aboard the SUVA out of her home port, the historic Coupeville Wharf.

The 20th century saw a popular rise in coastal fishing resorts, with family holidays taking place in summer camp-like settings on beaches all around the Sound. Camano Island was a very popular destination for these resorts, with 26 of them coming and going between 1921 and 1990. Visitors can still experience this bygone era with a day trip to Cama Beach Historical State Park. Important maintenance works are being carried out and no overnight stays or visits to the Center for Wooden Boats are available at this time, but rows of original beachfront cabins can be seen and beautiful foreshore walks enjoyed. Before the relatively recent fishing resort years, this site was believed to be a seasonal Coast Salish village with origins going back well over a thousand years.

Maritime heritage is still very much alive and felt today, with a vast number of Washingtonians still crossing parts of the Sound on a daily basis. The state ferry system is the largest in the country and among the largest in the world. Many exemplary boats found worldwide were built right on the shores of Holmes Harbor in Freeland. It’s fitting then, that the Maritime Washington National Heritage Area was designated in 2019; encompassing 3,000 miles of the state’s saltwater coastline and enveloping both Whidbey and Camano Islands.

Visit any of the museums featured in this guide to learn more about how the waterways surrounding Whidbey and Camano islands have been used since time immemorial.