by Elizabeth Guss

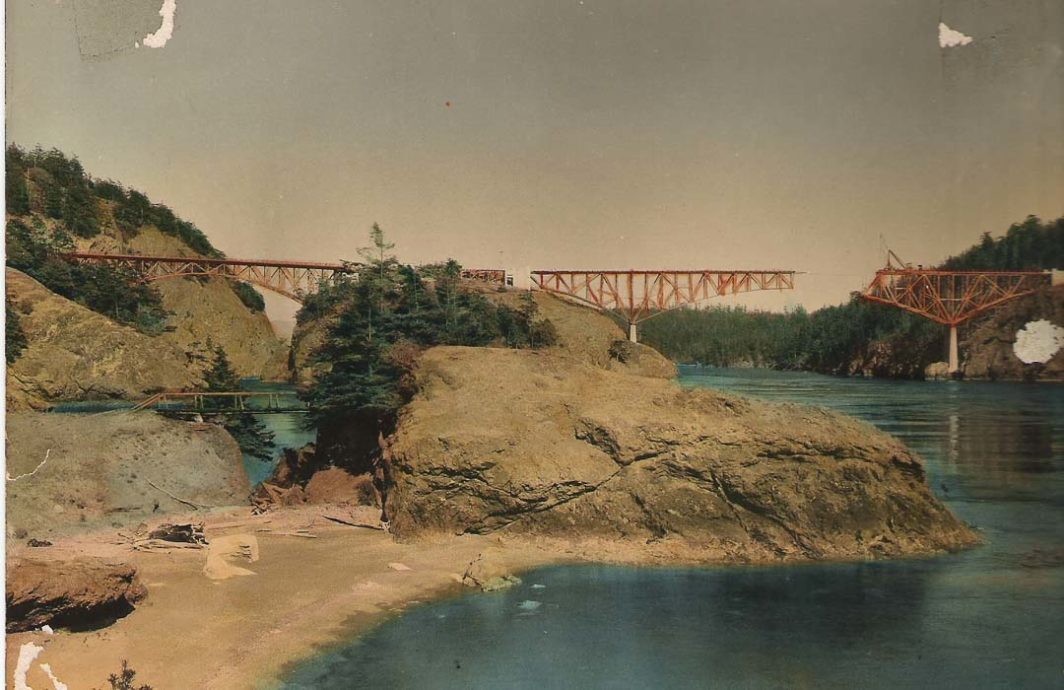

The Deception Pass Bridge began as a dream, became a convenience, and developed into an icon. Curving gracefully between Fidalgo and Whidbey Islands, it crowns the most visited state park in Washington. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982, this bridge is recognized for its engineering and elegant architecture that complements the scenic and geologic wonder of Deception Pass. Its history brings together the place, the people, and the popular park that draws visitors from around the world.

Finding Parking around Deception Pass…

There are several places you can park, get out, and enjoy Washington’s most popular state park. All parking is $10 a day or free with a Discover Pass.

Washington State Park Service Ranger Rick Blank is one of several folks who have guided visitors through the Deception Pass State Park. With 4,134 acres, 14.6 miles of saltwater shoreline, three lakes, and 35 miles of trails, this park has national park size and quality. Known for breathtaking views, old growth forests and abundant wildlife, its topography features rugged cliffs that drop to meet the swirling waters of Deception Pass. The park has historical interest and many varieties of landscapes. Yet, as Ranger Rick states, “When people think of Deception Pass, the first thing they think of is the bridge.”

This great achievement began with an idea from a New England seaman, Captain George Morse, who sailed through the narrow, turbulent waterway called Deception Pass and eventually settled in the tiny village of Oak Harbor on Whidbey Island. Pointing at the two promontories of Whidbey and Fidalgo in the 1880s, he told his children that “one day we will have a bridge across this pass with Pass Island as a center support.” Fifty years later, with the persistent work of citizens and legislators, and the public works support of the Great Depression, the bridge became a reality.

Some 700 cars traveled on the bridge on July 31, 1935, the day it was dedicated. About 20,000 cars now cross the bridge 180 feet above its swirling water every day. Dramatic and intriguing, the bridge is the Pass’s great connector. It links three islands together and interweaves history, recreation, commerce, nature and more.

Human history in the park dates back thousands of years when the first people settled in Cornet Bay, Rosario, and Bowman. They hunted, fished and harvested edible native plants like nodding onions. Shellfish middens are found in all these locations. Juan de Fuca may have been one of the first white explorers to visit the area in the late 1500s and the strait named for him marks his voyage. Nearly two centuries passed, however, before Deception Pass’s mysteries were revealed to the world.

Carved by glaciers, the steep cliffs and sharp edges of the islands create natural barriers and divert tides flowing from the Strait of Juan de Fuca past Whidbey and Fidalgo Islands. Deep, mist-shrouded forests add a touch of mystery to the appearance. Tidal flow can be extremely rough and low tides create standing waves, huge whirlpools and roiling eddies. With the small islands (Ben Ure, Strawberry and Pass) between them, Whidbey and Fidalgo Islands appeared to many early explorers to be sides of a small bay or perhaps the mouth of a river. It probably looked too dangerous to sail into the waters of the pass.

Spanish explorers of the late 18th century named many local landmasses, including Rosario and both Fidalgo and Camano Islands. In 1792, Captain George Vancouver spent months exploring the area. He, too, named many local features (Puget Sound, Admiralty Inlet, Mount Rainier, and Mount Baker). It was Vancouver’s chief navigator, Joseph Whidbey, who sailed into the pass and followed the water south into the Saratoga Passage, disproving the bay theory. Honoring his chief navigator’s courage and discovery, Vancouver named the island to the south of the pass after him: Whidbey.

European and U.S. settlers arrived in the mid-19th century and the pass entered a new era. Smugglers of people and goods found the waters and islands of Deception Pass good for their nefarious business dealings. With steep cliffs and craggy edges, the pass appeared to have strategic military value. In 1866, more than a thousand acres were set aside for a military reservation that was partially fortified during World War I. From 1910-14, a prison rock quarry operated on the eastern side of Fidalgo Island with barges taking the quarried rock to the developing Seattle waterfront. In the 1920s, the military sold its land to Washington State which set it aside for a park in 1923. Small boats ferried travelers between Fidalgo and Whidbey over the swirling waters of the Pass. To call the ferry, they banged a saw with a mallet, sat back and waited.

By 1900, the idea of a bridge increasingly gained popularity. Captain George Morse, new Oak Harbor representative to the state legislature, introduced a bill in 1907 appropriating $90,000 toward the building of the bridge. The area was studied and plans were drawn for two steel arches; a model was built and displayed at the Alaska-Yukon Expedition in Seattle (1909). In 1918, the bridge was promoted as a necessary war effort and in 1921 state legislators wrote an appeal to Congress citing its military importance. The American Legion helped form the Deception Pass Bridge Association which encouraged state legislators to pass the 1929 Bridge Bill. The bridge’s time was coming.

On another front, farmers in the Clover Valley of North Whidbey began building roads to the bridge approaches. The American Legion worked to activate local interest in the bridge project and the annual Cranberry Lake picnic was born. Hundreds came yearly to Cranberry Lake, the first picnic area in the Deception Pass Park, for fun, food and political speeches that encouraged citizens to continue their advocacy for a bridge.

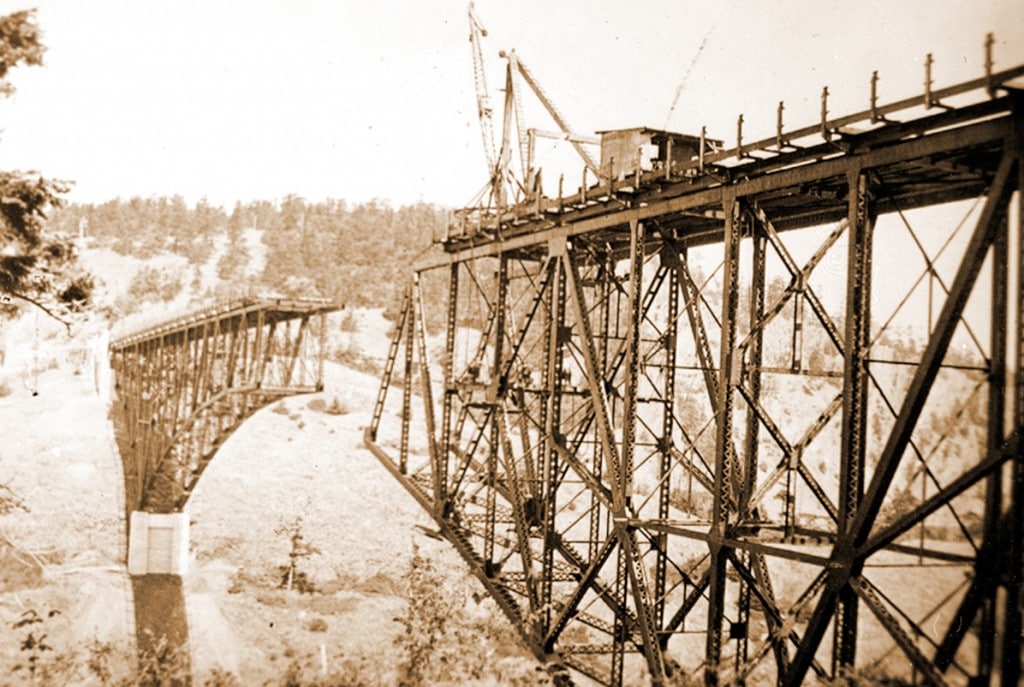

During the Great Depression, the Public Works Administration sent the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) to build park facilities and bridge approaches. The Park had rapidly become popular with residents of both Oak Harbor and Anacortes, yet had few facilities. Two CCC camps were established, one at Cornet Bay on Whidbey and one at Rosario on Fidalgo. About 200 young men built kitchen shelters, ranger residences, roadways, trails, restrooms and the log railings along the highway. In less than one year, from August 1934 to July 31, 1935, the bridge fabricator Puget Construction Company of Seattle built the two-span bridge. CCC workers helped build the road bed leading to the bridge.

The bridge is remarkable in many ways. The simple flowing lines of its arched steel structures complement the surrounding land and enhance the area’s visual drama. Its two sections, a 511 foot structure from Fidalgo to Pass Island and a 975 foot structure from Pass to Whidbey Island, show how the cantilever truss had evolved into an attractive, functional form. Twenty-eight feet wide, with two auto lanes and two sidewalks, it was built for $482,000 (a combined pool of Emergency Relief Administration, county and other federal funds).

First-time visitors usually see the bridge from their car. Equally impressive is the view from the beaches below. Above the water soars an achievement of vision and persistence – humans adding to nature’s scenic wonder. The bridge facilitated North Whidbey development, fostered the eventual placement of the Naval Air Station Whidbey in Oak Harbor, and became the local image that visitors thrill to see. Truly a crown, the Deception Pass Bridge has brought a new dimension of romantic flavor to this intriguing and majestic area.

Information in this story comes from a variety of sources, including: www.deceptionpassfoundation.org, www.deceptionpasstours.com, an interview with Ranger Rick Blank of Washington State Parks and Recreation, A Bridge over Troubled Waters: The Legend of Deception Pass by Dorothy Neil, South Whidbey Historical Society, Langley, WA 1999.

Discover Pass Fee Required:

The Discover Pass must be displayed on your vehicle when visiting state recreation lands managed by the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission, the Washington State Department of Natural Resources and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Park Hours:

Summer: 6:30 a.m. to dusk.

Winter: 8 a.m. to dusk.

Camping:

Check-in time, 2:30 p.m.

Check-out time, 1:00 p.m.

Quiet hours: 10:00 p.m. to 6:30 a.m.

For more information, visit their website.